As this planet completes yet another revolution around a pocket of spacetime curvature abounding with scintillating, mingling ions — and while the sparks seem to be flying in all of the wrong ways here on Earth — I wanted to share some thoughts on a few of the books I read this year. I will in no way do these works justice, but hopefully, I can convey some of the insights, joys, laughs, and tears that they brought me. To see a full list of the 53 books I read in 2023, head to my goodreads.

“E il naufragar m’è dolce in questo mare (and sweet to me is foundering in the sea)” – Giacomo Leopardi, via Italo Calvino

What is Existentialism? – Simone de Beauvoir

This book I read at the beginning of this year; it is composed of two essays: What is existentialism? and Pyrrhus and Cineas.

The philosophy under discussion is a response to the diverging threads of self-identity in christianity and marxism: in christianity we have the self, or the soul, as something separate from the world, aching to escape the world; while with marxism the human experience is not disentanglable from the physical world; Pascal referred to man as a “thinking reed”, engrained, waving in the ebbs and flows of life.

To quote Simone, existentialism “postulates the value of the individual as the source and reason for being [raison d’être]”. This philosophy combines individualism with marxist realism and bids us to be in the world and of the world; we can affect the world, just as we are an effect of the world.

I will leave off with a favorite quote of mine from the book, which is a rallying cry to all of us who have the urge to conquer something, like Pyrrhus, but are unsure of exactly why they should do so:

“Each new act of surpassing [dépassement] gives anew the thing surpassed, and that’s why technologies are ways of appropriating the world: the sky belongs to those who know how to fly; the sea belongs to those who know how to swim and navigate. Thus our relationship with the world is not decided from the onset; it is we who decide.”

The Cyberiad – Stanislaw Lem

It’s not possible for me to compare this book to anything else, it is pure brilliance that had me unable to control my laughter throughout. It is comprised of number of “sallies” where the brilliant constructors Trurl and Klapaucius are called upon for their prodigious talents. Turning now to a random page, to give a taste of this masterpiece, I find words such as “drasticodracostochastic control” and “discontinuous orthodragonality”.

It’s hard for me to describe this without spoiling details, so will not say much more, other than that you (the reader who has made it this far) should read this book. I’ll leave you with a bit of poetry that I found (in practice) that can impress attractive bartenders:

Ellipse of bliss, converge, O lips divine!

The product of our scalars is defined!

Cyberiad draws nigh, and the skew mind

cuts capers like a happy haversine.I see the eigenvalue in thine eye,

I hear the tender tensor in thy sigh.

Bernoulli would have been content to die

Had he but known such $a^2 \cos 2\varphi$!

This and much more awaits you in The Cyberiad.

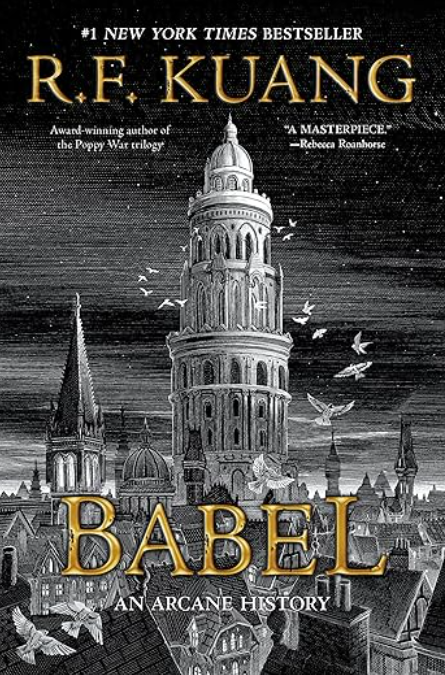

Babel – R. F. Kuang

I am not a big reader of fantasy (I would even admit this is the first book of fantasy I’ve read as an adult), but this book, while definitely fantastical in some regards, used the magic silver working aspect as a way to beautifully connect the art (and to some extent science) of language, etymology, and translation with the poignant realities of power, war, and the human urge to stand up to oppression.

I found myself enamored with the scholarly world of Oxford and the intriguing, inimical practice of translation. I learned to look at language in a new way — not least because I am currently trying to teach myself french and italian — while also being reminded of the power that language has to shape the world. The ancient battle between the tongue and the sword comes to a head in this story, and we are left to watch as decisions are made that we may never be capable of fully understanding. In light of recent events in the world, dealing with rhetoric and violence, it is a timely read, if only to grapple with analogous situations in a different context.

The Penguin Book of Jewish Short Stories – edited by Emanuel Litvinoff

The caliber of writing in this collection is astounding. In relation to the semi-fictional world of Babel, here we get to see first-hand accounts of people facing truly incomprehensible horrors and coming away from them. Wit, wisdom, and wiley humor are on full display in these stories which stretch from the pogroms of eastern Europe to fortune-making in the mid-twentieth century upstate New York real estate market.

This collection includes the stories of

- I. L. Peretz

- Sholem Aleichem

- Lamed Shapiro

- Abraham Reisen

- S. Y. Agnon

- Isaac Babel

- Isaac Bashevis Singer

- Emmanuel Litvinoff

- Aharon Appelfeld

- Dan Jacobson

- Philip Roth

- Saul Bellow

- Cynthia Ozick

- Amos Oz

- Bernard Malamud

- Muriel Spark

Millennia of knowledge and experience has been accumulated and put to paper by these authors and I can’t recommend this collection enough as a way to see the world through the eyes of a people who have been through so much, giving back all along the way, and have so much yet to give.

Six Memos for the Next Millennium – Italo Calvino

This collection of lectures — which includes just five, with the sixth, on consistency, being left unfinished — highlights the literary genius of Italo Calvino. While these lectures were written in 1985, they anticipated so well the world we live in today, and if anything, his words are more true now than ever.

Lightness

Italo begins by describing literature “as an existential function”, that is, “the search for lightness as a reaction to the weight of living”. The atomism, which Lucretius was so fond of, is used to illustrate the paradox — which still holds its validity today — of the lightness, and inert ephemerality, of the fundamental particles (or really fields) that yield atoms, chemistry, biology, and eventually, us. Via a Kafka story of a flying bucket, we are left, at the end of this lecture, with the fact that “the fuller it is, the less it will be able to fly.”

“Thus, astride our bucket, we shall face the new millennium, without hoping to find anything more in it than what we ourselves are willing to bring into it.”

Quickness

The essence of this attribute can be found by contrasting and comparing the Olympian messenger god Mercury (his metamorphoses, winged flights, and instantaneous expressiveness) with the craftsman god Vulcan (his deliberate, methodical, and painstaking perfectionism). Calvino tells us that “Mercury’s swiftness and mobility are needed to make Vulcan’s endless labors become bearers of meaning.” In other words, as a writer today, one needs to be as precise as possible, but also one needs to be able to terminate the process of creation in mercurial flourish, as time is of the essence.

Festina lente, hurry slowly

Exactitude

When dealing with the world via literature, we are faced with multitudinous (maybe even infinite) ways of describing phenomena. Science is of little help — our knowledge is inherently stratified, expanding, and incomplete. “The human mind cannot conceive the infinite, and in fact falls back aghast at the very idea of it, it has to make do with what is indefinite.” Utilizing language to achieve maximal clarity, or exactitude, is the challenge thus faced; words connect “the visible trace with the invisible thing, the absent thing, the thing that is desired or feared, like a frail emergency bridge flung over an abyss.”

This is no easy task, none other than Leonardo da Vinci filled his notebooks with iterated sentences, trying to grasp the essence of the thing he was contemplating. We should all learn to love and master this process.

“the real work consists not in its definitive form, but in the series of approximations made to attain it”

Visibility

In existing, in creating, at a certain point we all must “start putting black on white”. To stand out, we must be able to focus our own mind’s eye on the elements of our memories, sensations, and experiences that will enable us to realize the “world of potentialities”, that is our imagination. The problem is one of undecidablilty, that is, “the paradox of an infinite whole that contains other infinite wholes”.

In this year in particular, with the advent of generative AI, we are facing a whole new level to the challenge identified by Calvino with the question:

“Will the power of evoking images that are not there continue to develop in a human race increasingly inundated by a flood of prefabricated images?”

Multiplicity

This year seems to me as if humanity is finally coming to bat regarding the state of our knowledge of the world. Calvino in this essay defends the novel that attempts an encyclopedic scope (since the noun encyclopedia literally means an encircling of all knowledge, this is a bit paradoxical); each one comes up short in some way, but the attempt is a noble one.

The attempt by an author to grok (I will begrudgingly use the timely term) every field of knowledge and bring it into his creation in a way that does it justice is maybe the most honorable of all literary pursuits. In practice, this is infeasible unless one allows himself to be beholden to rules, that will allow him to tame the infinite. I won’t philosophize here on how this could apply to our society today, but I will end with a quote from Raymond Queneau, via Calvino:

“Now this sort of inspiration, which consists in blindly obeying every impulse, is in fact slavery. The classical author who wrote his tragedy observing a certain number of known rules is freer than the poet who writes down whatever comes into his head and is slave to other rules of which he knows nothing.”

Consistency

noun, conformity in the application of something, typically that which is necessary for the sake of logic, accuracy, or fairness

it., consistenza; fr., cohérence

Siddhartha – Hermann Hesse

Listen, to the river, and everything else.