Just about a year ago today, I began working on implementing an algorithm my undergrad research advisor had devised to speed up the Metropolis algorithm, in the regime where the acceptance probability is very low, which is the case in lattice simulations of quantum gravity.

Quantum Gravity

Physics has experienced its most rapid advancement when theories are unified:

- electromagnetism $\leftarrow$ electricity + magnetism + light

- general relativity $\leftarrow$ special relativity + curved space-time (gravity)

- quantum field theory $\leftarrow$ quantum mechanics + special relativity + electromagnetism + matter + nuclear forces

And hopefully soon…

- quantum gravity $\leftarrow$ quantum field theory + general relativity

It turns out the problem is pretty simple… to state. We just need to solve the following path integral:

$$ Z = \int \mathcal{D}g \exp \left(\frac{1}{16\pi G}\int d^4 x \sqrt{-g}(R - 2\Lambda) \right) $$

Ignoring for a moment the subtleties of evaluating a path integral in general, in this case it turns out that the term inside of the exponential, the Einstein-Hilbert action, causes some serious problems. $Z$ is perturbatively non-renormalizable, which is technical jargon that means the theory spits out infinities when we try to calculate simple interactions and those infinities only get worse when we attempt to “cancel them off”, which is a prescription that miraculously works in other (renormalizable) theories, like quantum electrodynamics.

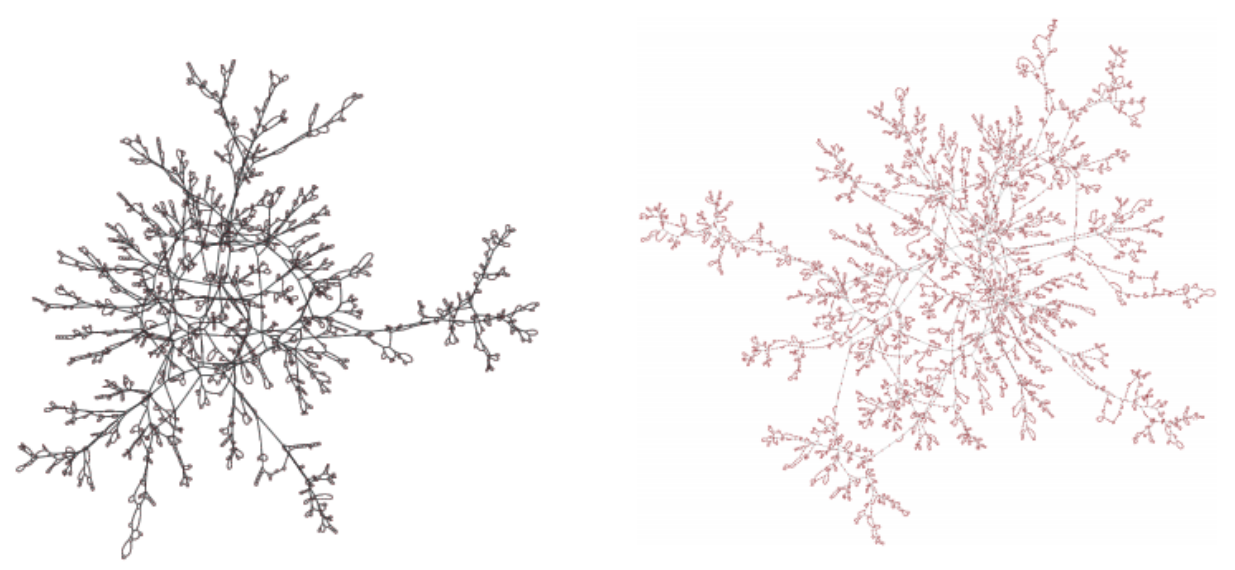

Hope remains though… while a perturbative expansion of $Z$ blows up, an idea known as asymptotic safety might save the day. This is what the group I became a part of is working on. More specifically we are using a computational technique called dynamical triangulation to calculate a discretized version of $Z$ on a lattice of 4-dimensional simplices.

The Freeman Method

The beauty of science is that every solution only leads to more problems… our new problem is that the algorithm we want to use to evolve our simplex lattice is inherently slow, or more accurately picky: it chooses to do nothing about 9,999 times out of every 10,000 times we ask it do something. Which is annoying!

The new algorithm basically goes as follows:

- think about every possible thing we could do and assign a number (probability) to each possibility

- imagine every possibility as a book on a shelf, with the width of the book corresponding to the probability of picking it

- blindly approach the book shelf and choose a book

This way, each time we want to do something, we actually do something. Which is great!

An implementation of this algorithm, in Julia, on the Ising model can be found on the projects page, or directly on github.

Slides and YouTube Recording

There are some more subtleties and technical points - if interested, details can be found in the slides of a presentation I made about this research, or, if very interested, you can also watch a recording of the presentation on YouTube by clicking (tapping) on the image below: